Silk weavers of Varanasi

November 28, 2009

I was a little bit nervous about going to Banaras (Varanasi) because I had no idea what we would find. I knew that Banarasi saris are famous in South Asia and beyond. I’d read a blurb in the Economist sometime before about how the silk weavers of Banaras have been devastated by changes in the global silk trade. But I didn’t really know how my idea could connect with this situation. Luckily, as happened so often on this trip, some great people helped us dive right in.

Amber’s friend Megan, a PhD student in anthropology, introduced us to Chris, an anthropologist who is doing an ethnographic study of the effect of globalization on the lives of Muslim traditional artisans in Varanasi. This is part of his larger research effort on how the Urdu language mushaira (poetry recital) impacts globalization and transnational processes on two South Asian Muslim communities: working class silk weavers in Varanasi, and South Asian expatriates in Saudi Arabia and Dubai. Needless to say, with his 10+ years of experience in the artisan communities of Varanasi, Chris offered us more information than we dreamed we’d learn in just a few days. Here’s a little bit of what we learned.

Banarasi silk has been famous across South Asia and the Middle East for hundreds of years. It is woven in six-yard saris with intricate designs, sometimes including real gold and silver thread (zari), for the most important social occasions. The sari forms may also be cut to create smaller items like scarves and pillow covers. Traditionally a Muslim trade, Mughal influences are often seen in Banarasi designs.

Today, however, it is estimated that Varanasi has lost 80% of its silk weavers, many of whom have left the city. The reason? A wave of cheap, machine-printed silk from China and synthetics made in Gujarat has rendered Banarasi silk uncompetitive in the global marketplace. With these lower-quality substitutes in easy reach, weavers with 15-20 years of experience can expect to make just $3 to $4 per day. As Chris told us, a cycle rickshaw driver can easily earn that wage.

We wondered if there were any cooperatives or unions working in favor of the weavers. But Chris told us that the Banarasi silk weavers’ union is known to be a political entity that serves its members poorly. And most middlemen pit weavers against each other and use the competitive situation to their advantage. So how could we get involved?

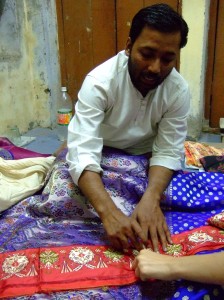

Chris suggested that we meet a family of middlemen he’s known for several years to be ethical in their dealings with weavers. So one evening, we visited the home of Daud, an elderly man whose sons Shahid (also a chemist) and Saud now run the family business. Saud, who is married and has two children, proceeded to give us an elementary introduction to silk weaving: the terminology, the techniques, the process from design to finished product, how to identify real silk and real gold in fabric. His family works with five weavers who use hand looms on which it takes two to four weeks to make a sari. Below are some pictures of what we saw.

Saud teaches us about silk.

A weaver at work on a Jacquard loom.

Punchcards on a Jacquard loom: a precursor to the development of computing hardware. Each set of cards controls the weaving of particular patterns. It takes up to 10 days to make a set of cards, and due to the peculiarity of looms, cards must be made to order for an individual loom.

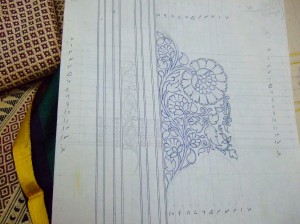

A penciled design for a brocade. This will be transferred to a large sheet of paper that shows the weft colors in magnified detail, which is then used by the weavers to create the design. We weren’t allowed to photograph those templates as they are considered proprietary.

Although saris with zari work are still made, like this Jora with faux metallic thread made for women marrying into a family of weavers, today only a score of weavers know the art of weaving with real gold and silver.

We’re very excited about the prospect of working closely with weavers in Banaras to help them preserve the legacy and develop the future of their art. Since we weren’t able to purchase anything from them on short notice, we bought some lovely finished products from another shop in town that employs a small number of silk weavers directly. You might say I got carried away with pillow covers, but I love them because they are simple yet luxurious accessories with a great story. I hope you’ll agree if you get to see them.

A few days in Varanasi

November 27, 2009

Upon our return to Delhi from Pakistan, we headed east to Varanasi (also known as Banaras) in Uttar Pradesh. Amber had spent a few months learning Hindi there in 2007, and in spite of adoring her teacher and his wife, she warned me that the city has the unsavory reputation in India of being among the country’s dirtiest and most tourist-ridden locales. It’s true that many Indian Hindus come to Varanasi to perform various religious rituals at the Ganges, but it seems that most would not want to live there.

Fortunately, trash burning was light while we were there (Delhi’s pollution was actually much worse), and while the number of tourists was a bit of a shock after Pakistan, we hardly felt like lemmings. Apparently the global economic crisis has affected tourism significantly. In any case, one has to arrive at a certain acceptance of the realities of refuse and the effects of tourism in India to avoid seething with disgust. So, we enjoyed the famous winding alleys and sunny ghats in relative peace. I even took a boat ride on the Ganges, during which my business-like guide chastised me for not going at sunrise like all the other tourists in order to watch the fascinating pujas and ogle local bathers. And my prosaic concern about pollution kept me from even dipping a toe in.

More on what we actually found in Varanasi in the next post – for now, a few photos.

View from our hotel: classic Banaras. It looks much older than it is, and temples are hidden in plain sight (that's one on the left).

With a closer look, we saw two boys flying (or attempting to fly) a kite. We saw quite a bit of kite flying in India as it was the month before Basant/Makar Sankranti, spring festivals celebrated around January 15. Kite flying is especially popular in Gujarat, where our father is from. (Kite flying is also popular in Pakistan, especially Lahore, but it was recently outlawed due to the practice of coating kite string with shards of glass or metal, which makes them formidable in kite fights but potentially dangerous for unsuspecting passersby).

Postcards from Pakistan

November 17, 2009

As my business idea developed, I knew I wanted to go beyond India. India dominates global awareness of the South Asian region, due to its size, its recent economic rise, and for Westerners, its alluring combination of accessibility and the exotic. Most of the other countries in the region are known for civil wars, extreme poverty, and natural disasters. Even the positive highlights (mountaineering in Nepal, microfinance in Bangladesh) are caricatures. I believe this does a disservice to the region as a whole, by reducing real problems to stereotypes and reinforcing problematic power dynamics – not to mention the personal consequences for families and communities living in ignored or divided societies.

I especially wanted to include Pakistan in my plan as, apart from the Kashmir conflict with India, it has largely been ignored by the rest of the world in my lifetime. That is, until the advent of the global war on terror cast it in an impossible leading role on the global stage. These days, Pakistan is generally known for terrorism and political instability but little else. Yet my sister lived there with her partner for about 10 months in 2007-2008, and she is passionate about the country and her experience there. So I wanted to see how we might be able to present a different perspective on Pakistan’s culture, at least in a small way.

We had just 11 days in Pakistan, mostly in Lahore. Too short a visit, but a good start. It is a beautiful country, easier to get to know than some other places precisely because it is overlooked by tourists. I look forward to returning. For now, here are some snapshots of the people and places we saw, and some of the good work that we hope to support.

The hospitality of Pakistanis is deservedly renowned. People who know you only through third and fourth degree connections are happy to offer any assistance they can. In Lahore we stayed with Shahid Uncle, our father’s colleague’s wife’s former-brother-in-law, for longer than is reasonable and had a lovely time.

The Family Welfare Cooperative of Lahore works with women and families in six katchi abadis (slums) as well as the surrounding villages of Pakistan’s cultural capital. Women have the opportunity to learn several trades, such as hairdressing, office administration, community organizing, and textile crafts. As part of the craft program, women learn to sew, embroider, and crochet, making sweaters, children’s clothing, tablecloths, and other linens. They are able to work at the training center or out of their homes. Most of these products are sold in local markets. My favorite purchases were children’s clothing – charming kurtis and dresses.

In addition, the FWC runs schools and a hospital providing low cost services to the poor in Lahore. In the villages surrounding Lahore, the FWC gives microcredit loans to women for raising cattle and water buffalo and operates a mobile health clinic.

Amber’s friend Imran took me out for breakfast one day in Lahore’s Walled City. The delicious halwa puri is all you could ask for in a top notch breakfast: something savory, something sweet, something fried, all fresh and accompanied by piping hot chai.

Imran is an artist with an uncommon philosophy. While many people agitate for change (and recognition as change leaders), Imran asks: What really needs to change? And what can you honestly do about that? He is not an apologist for indifference. Rather, he sees the beauty and vibrancy of many situations (like Pakistan’s socioeconomic milieu) where others see only a need for change. After all, in such an oppressive society as Pakistan’s you can openly hold hands with a friend of the same sex without the assumption of homosexuality, you can be the recipient of a blessing from someone who recognizes your need, and you can be sure that relationships are valued above all else. Imran believes it is most important to be present in every moment, giving of yourself fully and honestly to those around you – that is how the world evolves.

Imran also took me to visit the Naqsh School of Arts, started in 2003 by a foundation to provide affordable education in the arts. The school offers a three-year certificate course in drawing, painting, ceramics, sculpture, illustrations, wood carving, fresco and design at a cost of less than $5 per month for students. The students were studying drawing that day, and I would have loved to purchase some of their works. But the school keeps all the students’ works for its own use as part of the fee – a big problem for budding artists who need to learn how to market their works. However, Imran is involved in another project called Dugdugi, which has the goal of making art created by low and middle income artists affordable for the average Pakistani. I hope to purchase some of these works for sale in my shop later on.

By chance Amber and I found Hunza Gallery and Kaarvan Crafts in Islamabad. Both shops benefit artisans in northern Pakistan. Mahmood is from Hunza and works in the tourism industry. His company sponsors Hunza Gallery, which is dedicated to supporting artisans working in Hunza, surrounded by the beautiful Karakoram mountains in Pakistan’s Northern Areas. Sharing borders with China, India, and Afghanistan, this area has a unique culture. Apricots are an important food source and make their way into all kinds of dishes from soup to dessert, as well as soaps, oils, and wood products made from various parts of the apricot tree. The cold weather in the region has led to specialization in wool and leather products like hats and jackets (like the one Mahmood is wearing), as well as rugs and other accessories.

Kaarvan promotes the economic empowerment of women by developing and marketing their high quality, handmade products. Traditional skills such as embroidery and beadwork are preserved while women gain self-sufficiency through home based work. Kaarvan started with a group of women entrepreneurs near Lahore, producing handmade cards which won a Body Shop competition and earned the program some seed capital.

As of 2008, Kaarvan has served over 2,500 women across Pakistan and sells their products through four fair trade shops in Pakistan. My favorite purchases here were handbags – lots of fun and creative designs.

Also in Islamabad, I met with Asma Ravji of the Sungi Development Foundation. Amber and I visited their shop as well; my favorite products were crocheted shawls and handmade embroidered cards.

Sungi works in the Northwest Frontier Province of Pakistan to promote the empowerment of women within a broader socioeconomic context. Starting with a development plan for an entire village, Sungi earns the trust necessary for a true partnership by working with the community on a basic needs infrastructure project. The next step is an economic development program in which women are encouraged to develop their existing craft skills through home based work. Beginning with training and materials provided by Sungi, the women progress to making crafts independently and selling them not just to Sungi but to other local buyers, with marketing and business development support from Sungi. The women develop the entrepreneurial skills, financial means, and personal independence they need to strengthen their position in their homes and communities. This has led to increased education of girls (as mothers have the means to pay for it themselves), increased political participation by women (including to elected seats), and more pleasure in life (disposable income brings freedom and fun).

Samad has a small shop at the Lok Virsa Museum of Culture just outside Islamabad. Though he now lives with his family in Rawalpindi, he is from a village in the Northern Areas of Pakistan. The region is well known for its precious and semiprecious stones, and Samad uses sunstone, lapis lazuli, amazonite, serpentine, amethyst, and many others in his jewelry. The region also used to be part of the Silk Road, connecting China with Central Asia and the Subcontinent. It still sees some of the traditional trade patterns, and Samad uses Chinese freshwater pearls in his jewelry.

Testing the Waters

November 6, 2009

Right now I’m on a one-month trip through parts of Pakistan and India. This is a reconnaissance trip of sorts – My sister and I are spending a bit of time in a lot of places to find out if and where the idea I have can work out on the sourcing side. We are doing as much networking as we can, meeting with people who have some connection to the arts, to organizations supporting economic empowerment of the poor, and to the preservation of craft traditions. We’re also buying some sample goods for a bit of market testing in Seattle. In the weeks that follow I’ll let you know what we find out.